Georgie

Georgie (A Short Story of Fiction)

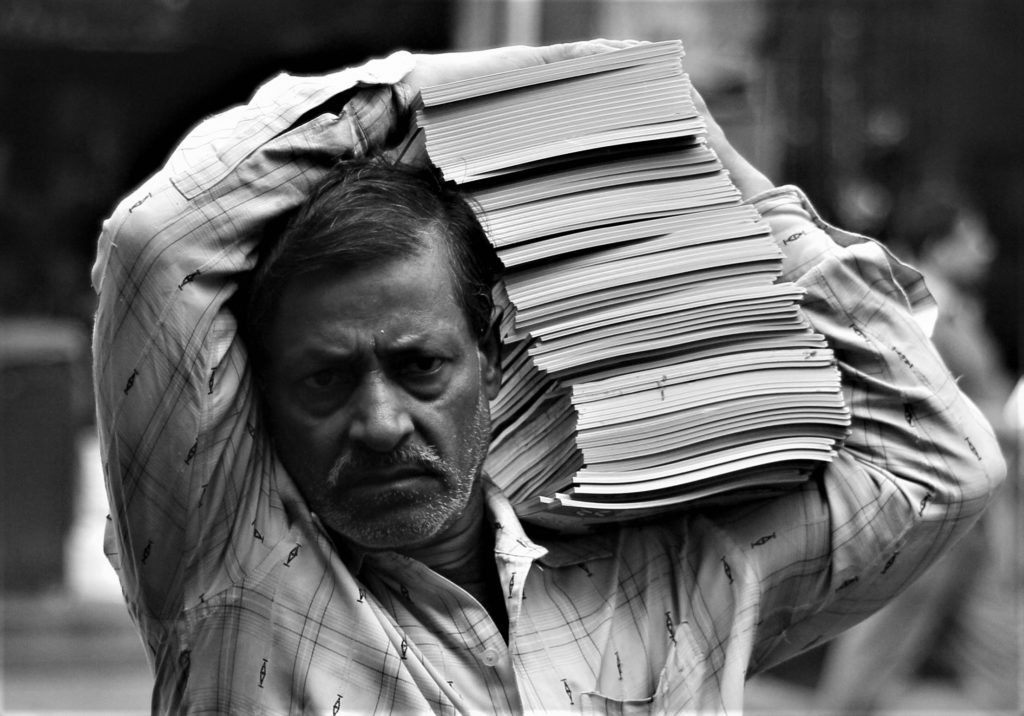

The old man’s arm curled up and over the back of his headrest. His skin was tar brown and stretched thin over ligament and bone. Gnarled fingers formed a hand that looked more like the burl of an ancient tree than an appendage that could move freely. His hand rested there, ten or so inches from my face. I wondered if he had diabetes or some other disease that limited feeling. Wondered as much because after seeing it dangling there in front of me for thirty minutes, I became curious and draped my own arm over the back of my own seat. It tingled within minutes. Then came the pain, and then I recoiled my arm to a more natural position. That was enough for me.

The man was old, maybe older than my own grandfather. It was hard to tell. Everything I knew of the man in train seat 17B I knew only of him from the elbow down. Maybe a little more than that, from when I caught glimpses of his leathery upper arm a few inches above the joint. He was probably a farmer, skin weathered the way it was. Grandpa was a farmer. Sort of. More like he was moved to a farm when he was twelve. Moved because his mother hated him. So she sent him to her sister, his Aunt. Claimed she was dying and could no longer care for her youngest. It worked until he was old enough to leave for the war and Mother all of a sudden never mentioned being sick again.

Underneath the old man’s fingernails was dirt and grime and soil. The kind that can’t ever be entirely cleaned out. Strata layers so infinitesimally thin I can only assume they were there, stacked up and compressed with each additional clawing through the dirt. My own grandfather’s fingers were long-since-destroyed by the time I was old enough to know him. The payment for five years on the farm, four in the service as an airplane mechanic, and then four decades on an automobile assembly line in Illinois: four fingernails, two fingertips, and two segments from his left pinky.

When he was on the farm, Grandpa George — or Georgie as his Aunt called him to emasculate him whenever she could — did all the chores. If Auntie was going to take him and raise him for her sister, she was going to get something out of it. So she worked him to the bone. George did his fair share of work around the farm. He also did most of the other kids’ fair shares so they could go to school. He would wake up with the roosters and work straight through the day until he was so tired that he would fall asleep before dinner. Which was fine by Auntie, because it meant she didn’t have to waste food on him that day.

Auntie’s husband had died in the great war, leaving her and her three boys and girl alone on their farm in southern Illinois. They somehow scraped by, “by the grace of God,” she would say, until two of the boys were old enough to work the fields and the stables. Then George came along and took over, allowing them to focus on trade school. Years later, it was discovered it wasn’t just the sons he replaced. I never learned the details. I don’t even think anyone remembers how it was found out. All I know is that, while George was fixing planes in the south Pacific somewhere around ‘44, his mom learned that her sister had been forcing George to have sex with her since he was thirteen. She had missed the touch of her husband. That was her excuse. It was the last time the sisters spoke to each other for twenty-seven years, until one day running into each other at the grocer.

“Hello, Liza,” Auntie said.

“Don’t you dare, you disgusting pig.” George’s mother said. Rumor has it she then threw a carton of eggs, ruining Auntie’s favorite weekday dress and bonnet. The entire situation was terrible, but it also seemed to me strange she reacted with such vitriol. After all, Liza disliked her son so much, she relinquished all responsibility and sent him off to the farm. Meanwhile, she treated her two girls equal parts princess and living doll. Grandma said she would dress them up identically to her, leading the miniatures around town like a mother duck leading ducklings.

The old man’s thumb twitched repeatedly. It was the first movement I had seen from him in an hour. Grandpa’s fingers would tremor like that. He’d be sitting at the table with us, silent as usual, and a finger or two would go haywire. Sometimes his pinky stump would throb up and down while he sipped his dinnertime can of Miller. I assumed it was from old age. Maybe it was from all those years working with his hands. Probably both. I don’t think anyone else at the table ever noticed, but when I was little, it would make me giggle to see his fingers vibrate like that.

An unexpected anxiety sprouted inside my gut like a rotten weed. I looked at the map on my phone. Thirty more minutes. I had asked Mom if Grandpa’s two cousins would be at the funeral. Auntie’s two surviving sons. Both, coincidentally, the two who beat my Grandpa the most. Grandma, when she was still alive, said they’d sometimes use a hollow metal rod leftover from a fencing job and whip his legs until he couldn’t walk. Then Auntie would order him beat again the next morning when he couldn’t do his work. Mom had said she didn’t know if the cousins would be there, but to be nice if they were. That it was a long time ago, and that they were old now, and that I shouldn’t upset them. But that’s Mom. Always trying to keep the peace. I didn’t know anything about the cousins, though, beyond the stories of how they tormented my grandfather when they were all young men. Maybe I shouldn’t upset them. Maybe they turned out to be good people. Maybe they won’t even show.

Gradually, the train slowed. I checked the time. Still too soon for my stop. The old man, however, withdrew his arm, and then braced himself on his armrests. He pushed up, up, up until finally standing like a crooked old tree twisted from years of wind. It was the longest I believe I’ve ever seen someone take to stand up. The back of his head had a scattering of fine white hairs and his earlobes drooped like melted candle wax. I wanted to see what he looked like from the front. See if he resembled my own Grandpa in ways not just related to being old and broken down by the labors of survival. The thought sucked me into a vision of the ceremony I’d soon be at. Would Grandpa look like I remembered? Thick brow, gigantic hook nose, and patchy white stubble he hated to shave clean? Or would what was in the coffin be only a plastic resemblance, like a bad wax statue of a celebrity?

Shuffling off the train without a bag or companion, the old man slipped in to the line of exiting folks. I craned my neck, poking out through the window, watching him move slowly and ungracefully toward the station, rivers of faster moving people flowing around him as if he were a stationary rock in a rushing creek. I watched for many minutes while he struggled to keep the pace of his left leg with his slightly limping right. Across the platform and up three stairs that looked so difficult for him to ascend I thought of the fact that I had never even considered how three steps could be anything more than a slight inconvenience. He stopped, and for a moment looked as if he would turn back toward the train. But he didn’t, and then he was gone. I never saw his face.

Michael Jackson. All of a sudden, I was yanked into the riptide and was being represented by one of the biggest talent agencies in the world. They set up an audition for us to pitch to an animation house to partner with, and Jay and I met up with a guy named Chapman, who was their point person. We met, we talked, we met again, we waited, we met a third time, and then they told us they were pumped and wanted to join us. It was exciting times. Chapman promised to have three different styles of sketches for us to choose from and we would go from there.

Michael Jackson. All of a sudden, I was yanked into the riptide and was being represented by one of the biggest talent agencies in the world. They set up an audition for us to pitch to an animation house to partner with, and Jay and I met up with a guy named Chapman, who was their point person. We met, we talked, we met again, we waited, we met a third time, and then they told us they were pumped and wanted to join us. It was exciting times. Chapman promised to have three different styles of sketches for us to choose from and we would go from there. episode summaries, artwork, etc. After many drafts, we worked the written content into something we could swirl together with the art, and our bible was complete. We showed it to our agency, they liked what they saw, and they began setting up meetings with TV networks to see if we could sell “The Adventures of Skweezy Jibbs.”

episode summaries, artwork, etc. After many drafts, we worked the written content into something we could swirl together with the art, and our bible was complete. We showed it to our agency, they liked what they saw, and they began setting up meetings with TV networks to see if we could sell “The Adventures of Skweezy Jibbs.” maelstrom of stress. Tragedy pulled from one side, and the pressure cooker of “this is my shot to make it big” pulled from the other. All that heaviness crushed any patience I had for inane customer interactions at my day job and one day I snapped. I was at the store and some asshole came in, stormed up to me, put his phone in my face, and whined “Fix this.” Without caution or pause, I threw my EZ Pay to the floor and marched to the break room. I didn’t bother going back out for an hour, but he was such a self-absorbed asshole and the store was so chaotic that no one even noticed that I had thrown my little fit and that was just as telling that I needed to fucking leave. I quit the next morning.

maelstrom of stress. Tragedy pulled from one side, and the pressure cooker of “this is my shot to make it big” pulled from the other. All that heaviness crushed any patience I had for inane customer interactions at my day job and one day I snapped. I was at the store and some asshole came in, stormed up to me, put his phone in my face, and whined “Fix this.” Without caution or pause, I threw my EZ Pay to the floor and marched to the break room. I didn’t bother going back out for an hour, but he was such a self-absorbed asshole and the store was so chaotic that no one even noticed that I had thrown my little fit and that was just as telling that I needed to fucking leave. I quit the next morning. want to be there anymore, so I left. I lived on, and did new things, and met new people, and got older and I realized it’s experiences like this past weekend that are what life is all about, and that’s why I make them happen as much as possible. But this isn’t an essay on cliched philosophical meanderings.

want to be there anymore, so I left. I lived on, and did new things, and met new people, and got older and I realized it’s experiences like this past weekend that are what life is all about, and that’s why I make them happen as much as possible. But this isn’t an essay on cliched philosophical meanderings.